| Title |

Reanimating and rematriating WRAP (MMU, thematic analysis teaching session)

Reanimating and rematriating WRAP (with staff and students at Manchester Metropolitan University):Documentation of a thematic analysis teaching session using data from the Women, Risk and AIDS Project (WRAP)

|

| Description |

In 2019-2020 the ESRC funded 'Reanimating data: experiments with people, places and archives'. Part of the project involved staging a series of reanimations using data from interviews with young women from Manchester, conducted thirty years previously as part of the Women, Risk and AIDS Project (WRAP 1988-1990). Each reanimation involved a collaboration between young women, educators and researchers and used creative methods to explore the WRAP data and bring it to life in new ways.

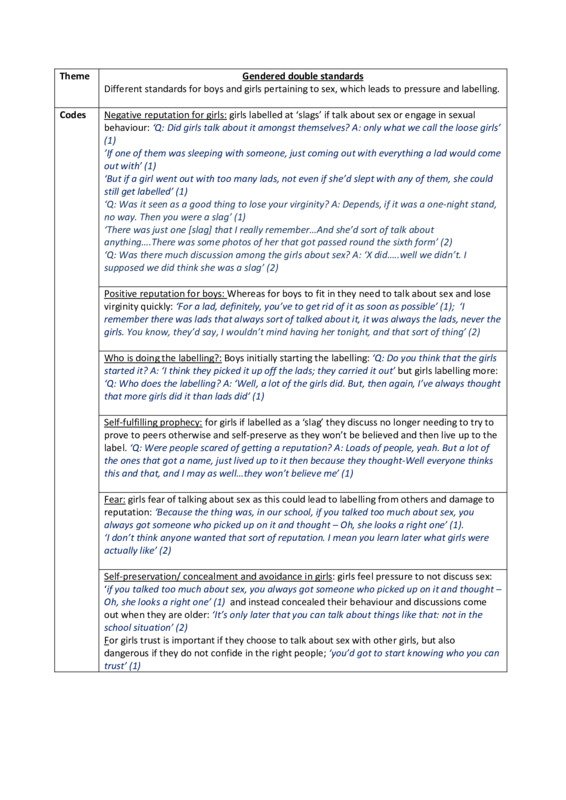

As part of the project the team supported two members of staff at Manchester Metropolitan University (Charlotte Bagnall and Claire Fox) to use two WRAP interviews (NMC12 and MAG12) to teach thematic analysis methods to their students. Charlotte and Claire analysed the data ahead of the session and identified two key themes: gendered double standard and basic or limited sex education. These themes were further explored by students. The zip file contains: * A blog by Charlotte Bagnall explaining how they worked with the data an delivered the session. * Written discussion of the gendered double standard theme by Charlotte Bagnall and Dr. Claire Fox. * Written discussion of the basic / limited sex education theme by first year student Angel Mellor-Davis. * Coding table for the gendered double standard theme. |

| Identifier |

MMU04/O

|

| Date |

Feb-20

|

| Creator |

Reanimating Data Project

|

| Publisher |

Reanimating Data Project

|

| Subject | |

| Type |

Text, Image

|

| Temporal Coverage |

2019

|

| Spatial Coverage |

Greater Manchester, UK

|

| Rights |

CC BY-NC 4.0

|

| extracted text |

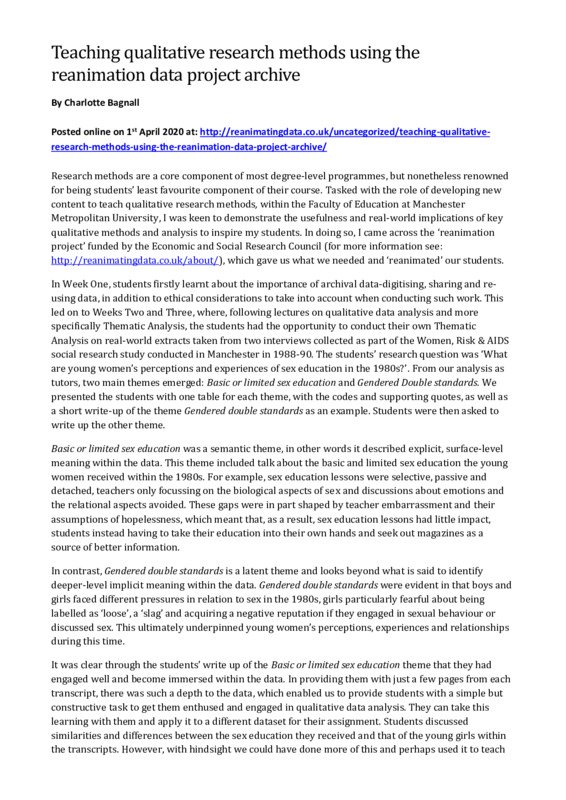

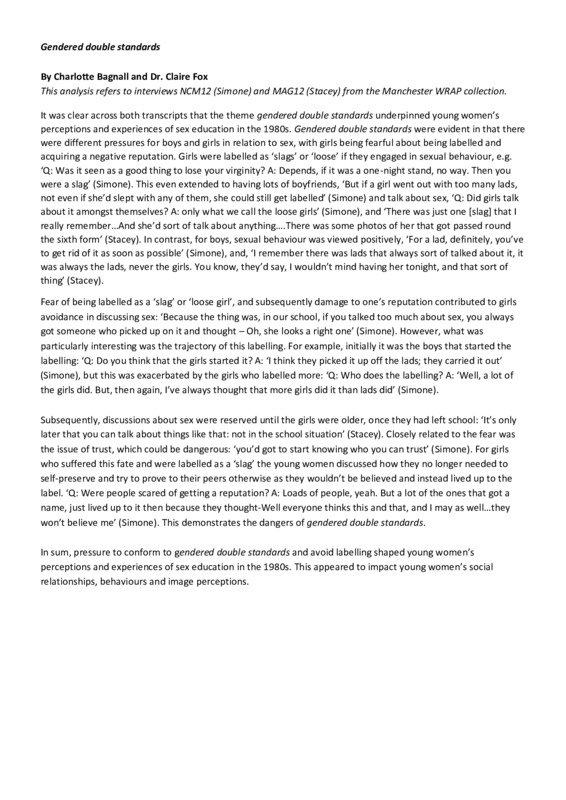

Theme

Gendered double standards Different standards for boys and girls pertaining to sex, which leads to pressure and labelling. Codes Negative reputation for girls: girls labelled at ‘slags’ if talk about sex or engage in sexual behaviour: ‘Q: Did girls talk about it amongst themselves? A: only what we call the loose girls’ (1) ’If one of them was sleeping with someone, just coming out with everything a lad would come out with’ (1) ‘But if a girl went out with too many lads, not even if she’d slept with any of them, she could still get labelled’ (1) ‘Q: Was it seen as a good thing to lose your virginity? A: Depends, if it was a one-night stand, no way. Then you were a slag’ (1) ‘There was just one [slag] that I really remember…And she’d sort of talk about anything….There was some photos of her that got passed round the sixth form’ (2) ‘Q: Was there much discussion among the girls about sex? A: ‘X did…..well we didn’t. I supposed we did think she was a slag’ (2) Positive reputation for boys: Whereas for boys to fit in they need to talk about sex and lose virginity quickly: ‘For a lad, definitely, you’ve to get rid of it as soon as possible’ (1); ‘I remember there was lads that always sort of talked about it, it was always the lads, never the girls. You know, they’d say, I wouldn’t mind having her tonight, and that sort of thing’ (2) Who is doing the labelling?: Boys initially starting the labelling: ‘Q: Do you think that the girls started it? A: ‘I think they picked it up off the lads; they carried it out’ but girls labelling more: ‘Q: Who does the labelling? A: ‘Well, a lot of the girls did. But, then again, I’ve always thought that more girls did it than lads did’ (1) Self-fulfilling prophecy: for girls if labelled as a ‘slag’ they discuss no longer needing to try to prove to peers otherwise and self-preserve as they won’t be believed and then live up to the label. ‘Q: Were people scared of getting a reputation? A: Loads of people, yeah. But a lot of the ones that got a name, just lived up to it then because they thought-Well everyone thinks this and that, and I may as well…they won’t believe me’ (1) Fear: girls fear of talking about sex as this could lead to labelling from others and damage to reputation: ‘Because the thing was, in our school, if you talked too much about sex, you always got someone who picked up on it and thought – Oh, she looks a right one’ (1). ‘I don’t think anyone wanted that sort of reputation. I mean you learn later what girls were actually like’ (2) Self-preservation/ concealment and avoidance in girls: girls feel pressure to not discuss sex: ‘if you talked too much about sex, you always got someone who picked up on it and thought – Oh, she looks a right one’ (1) and instead concealed their behaviour and discussions come out when they are older: ‘It’s only later that you can talk about things like that: not in the school situation’ (2) For girls trust is important if they choose to talk about sex with other girls, but also dangerous if they do not confide in the right people; ‘you’d got to start knowing who you can trust’ (1) Teaching qualitative research methods using the reanimation data project archive By Charlotte Bagnall Posted online on 1st April 2020 at: http://reanimatingdata.co.uk/uncategorized/teaching-qualitativeresearch-methods-using-the-reanimation-data-project-archive/ Research methods are a core component of most degree-level programmes, but nonetheless renowned for being students’ least favourite component of their course. Tasked with the role of developing new content to teach qualitative research methods, within the Faculty of Education at Manchester Metropolitan University, I was keen to demonstrate the usefulness and real-world implications of key qualitative methods and analysis to inspire my students. In doing so, I came across the ‘reanimation project’ funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (for more information see: http://reanimatingdata.co.uk/about/), which gave us what we needed and ‘reanimated’ our students. In Week One, students firstly learnt about the importance of archival data-digitising, sharing and reusing data, in addition to ethical considerations to take into account when conducting such work. This led on to Weeks Two and Three, where, following lectures on qualitative data analysis and more specifically Thematic Analysis, the students had the opportunity to conduct their own Thematic Analysis on real-world extracts taken from two interviews collected as part of the Women, Risk & AIDS social research study conducted in Manchester in 1988-90. The students’ research question was ‘What are young women’s perceptions and experiences of sex education in the 1980s?’. From our analysis as tutors, two main themes emerged: Basic or limited sex education and Gendered Double standards. We presented the students with one table for each theme, with the codes and supporting quotes, as well as a short write-up of the theme Gendered double standards as an example. Students were then asked to write up the other theme. Basic or limited sex education was a semantic theme, in other words it described explicit, surface-level meaning within the data. This theme included talk about the basic and limited sex education the young women received within the 1980s. For example, sex education lessons were selective, passive and detached, teachers only focussing on the biological aspects of sex and discussions about emotions and the relational aspects avoided. These gaps were in part shaped by teacher embarrassment and their assumptions of hopelessness, which meant that, as a result, sex education lessons had little impact, students instead having to take their education into their own hands and seek out magazines as a source of better information. In contrast, Gendered double standards is a latent theme and looks beyond what is said to identify deeper-level implicit meaning within the data. Gendered double standards were evident in that boys and girls faced different pressures in relation to sex in the 1980s, girls particularly fearful about being labelled as ‘loose’, a ‘slag’ and acquiring a negative reputation if they engaged in sexual behaviour or discussed sex. This ultimately underpinned young women’s perceptions, experiences and relationships during this time. It was clear through the students’ write up of the Basic or limited sex education theme that they had engaged well and become immersed within the data. In providing them with just a few pages from each transcript, there was such a depth to the data, which enabled us to provide students with a simple but constructive task to get them enthused and engaged in qualitative data analysis. They can take this learning with them and apply it to a different dataset for their assignment. Students discussed similarities and differences between the sex education they received and that of the young girls within the transcripts. However, with hindsight we could have done more of this and perhaps used it to teach students about ‘reflexivity’. It has been great to be part of this project and use the data to the benefit of our students, and I am looking forward to involvement in further projects stemming from reanimating data. Gendered double standards By Charlotte Bagnall and Dr. Claire Fox This analysis refers to interviews NCM12 (Simone) and MAG12 (Stacey) from the Manchester WRAP collection. It was clear across both transcripts that the theme gendered double standards underpinned young women’s perceptions and experiences of sex education in the 1980s. Gendered double standards were evident in that there were different pressures for boys and girls in relation to sex, with girls being fearful about being labelled and acquiring a negative reputation. Girls were labelled as ‘slags’ or ‘loose’ if they engaged in sexual behaviour, e.g. ‘Q: Was it seen as a good thing to lose your virginity? A: Depends, if it was a one-night stand, no way. Then you were a slag’ (Simone). This even extended to having lots of boyfriends, ‘But if a girl went out with too many lads, not even if she’d slept with any of them, she could still get labelled’ (Simone) and talk about sex, ‘Q: Did girls talk about it amongst themselves? A: only what we call the loose girls’ (Simone), and ‘There was just one [slag] that I really remember…And she’d sort of talk about anything….There was some photos of her that got passed round the sixth form’ (Stacey). In contrast, for boys, sexual behaviour was viewed positively, ‘For a lad, definitely, you’ve to get rid of it as soon as possible’ (Simone), and, ‘I remember there was lads that always sort of talked about it, it was always the lads, never the girls. You know, they’d say, I wouldn’t mind having her tonight, and that sort of thing’ (Stacey). Fear of being labelled as a ‘slag’ or ‘loose girl’, and subsequently damage to one’s reputation contributed to girls avoidance in discussing sex: ‘Because the thing was, in our school, if you talked too much about sex, you always got someone who picked up on it and thought – Oh, she looks a right one’ (Simone). However, what was particularly interesting was the trajectory of this labelling. For example, initially it was the boys that started the labelling: ‘Q: Do you think that the girls started it? A: ‘I think they picked it up off the lads; they carried it out’ (Simone), but this was exacerbated by the girls who labelled more: ‘Q: Who does the labelling? A: ‘Well, a lot of the girls did. But, then again, I’ve always thought that more girls did it than lads did’ (Simone). Subsequently, discussions about sex were reserved until the girls were older, once they had left school: ‘It’s only later that you can talk about things like that: not in the school situation’ (Stacey). Closely related to the fear was the issue of trust, which could be dangerous: ‘you’d got to start knowing who you can trust’ (Simone). For girls who suffered this fate and were labelled as a ‘slag’ the young women discussed how they no longer needed to self-preserve and try to prove to their peers otherwise as they wouldn’t be believed and instead lived up to the label. ‘Q: Were people scared of getting a reputation? A: Loads of people, yeah. But a lot of the ones that got a name, just lived up to it then because they thought-Well everyone thinks this and that, and I may as well…they won’t believe me’ (Simone). This demonstrates the dangers of gendered double standards. In sum, pressure to conform to gendered double standards and avoid labelling shaped young women’s perceptions and experiences of sex education in the 1980s. This appeared to impact young women’s social relationships, behaviours and image perceptions. Basic or limited sex education Angel Mellor-Davis, Year 1 Educational Psychology, MMU This analysis refers to interviews NCM12 (Simone) and MAG12 (Stacey) from the Manchester WRAP collection. Another prevalent theme in the transcripts was ‘basic or limited sex education’. The young women detailed the amount and depth of the sex education they received within Catholic school in the 1980s. The idea of basic or limited sex education was shown by mentions of few lessons given, e.g. ‘we got a lesson once’ (Simone) and ‘there was no sex education at all’ (Stacey). Teachers would rush over lessons, or miss out crucial information. ‘She didn’t really go into detail; she just went very fast. So we didn’t have much time to think’ (Simone) and ‘she just said – you can’t get AIDS from this, you can get it from this’ (Simone). Sex education largely had a biological focus, as opposed to informing students about safe sex. ‘Yeah, just like how babies are made, and that’s it’ (Simone), ‘Q: Did they talk about contraception? A: No’ (Simone). Students were not informed about the ways to prevent pregnancy or transfer of STIs: ‘Q: So did she say that if you use a condom you’ll be protected? A: No way’ (Simone) and ‘Q: Did they talk to you about contraception and STDs at school? A: No, nothing like that’ (Stacey). Furthermore, teachers did not explain relationship dynamics, or what emotions may arise when a student became sexually active, e.g. ‘nobody ever talked to you about the problems and the entanglements, and what it means to be in a relationship when you start having sex’ (Stacey). The girls also noted that any sex education they did receive only involved the teacher giving a short session of ‘just the basics’ (Simone), with no time allotted for further discussion or an opportunity to ask questions. ‘All we did was read from a book. We didn’t really discuss it or anything’ (Simone). Sex education for the general student population was described to be a bare minimum. Some further education would be given if students opted to study biology; ‘only if you took biology in the fourth or fifth year, we did quite a bit’ (Simone). The feelings towards sex education within biology in later school years seemed to be more positive, with more extensive education on how the body works: ‘I learnt a lot from biology, you know, about sort of …and the insides and things’ (Stacey). However, this more detailed teaching was reserved only for those who chose to study biology, and was not offered to other students. The basic or limited sex education led to students having to take their education into their own hands. Girls would seek out magazines as a source for better information, namely ‘man and woman’. Stacey explained that ‘we read them all! I think I learned a lot off that’. School sex education sessions left large gaps that the girls filled independently outside of school. Overall, the girls explained that they received quite poor sex education. Between teachers rushing lessons, and only providing factual information, to more information being kept back from the wider student body, and only being taught to fulfil the exam curriculum, students’ sex education was basic and limited. |